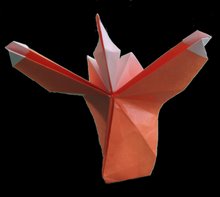

Frequently people ask me about what kind of paper I prefer to fold one or another model, if I have a preferred generic one, or if there is a "traditional" or "classic" paper from Japanese origami and what gives it its "special" condition. Then I gave answers like "to complex figures and very detailed is better to use tissue foil ", or "if I want the models to keep their shape in time you can use metalized paper", or "kraft paper is good if you want to wetfold or fold with brush". And everybody get happy thinking how much I know about this handcraft; everybody except me of course who realize that in fact I don't have a clue about what paper is, nor how it works, or why it has this or that quality.

How much knows an origamist about the paper he uses, how it was made, what's the secret that keep it tight and how to select the best for their purposes? And what about the making processes of paper and the ecological problems they mean to nature?

So I decided to do some research.

Maybe a good starting-point should be what paper is not. Word came from latin papirus which signed the plant which were used by the egipcians to make their famous writing rolls .. However, yet the principle is the same, paper we know and use today doesn't have its origins there. Papirus is a plant with long leafs, soft stalk and a triangular wide base and the rolls were made directly from its medulla, a paste which is spread over molds and hydrated with water, pressed and the left dry, to finally be rubbed with ivory or shell to soften its surface. Its origins goes back until 3000 BC and its use s to Greece and the entire Rome Empire until the Vth century. After that, writing was done over parchments, made from fine layers of cow, sheep or ram leather(1).

The true origin for paper lies on China. Around AD 105, emperor Ho Ti ordered his eunuchs chief Tsai Lun the study of new materials for writing, since the wood tablets and silk patches were unpractical for the growing usage of writing. His work concluded with the making of a vegetable pulp made with fibers from bamboo cane, mulberry and other plants, along with the development of a procedure for the making of the paper, which was kept absolutely secret for more than 500 years.

Only after AD 500 the technique of paper making passed to Korea and in AD610, priest Ramjing traveled to Japan for bringing assessment in the production of paper; both countries will upgrade it according to their own resources and technology (in AD700 rice flour was added to the pulp). In 750 it passed to Central Asia, Tibet and India, to finally reach the Arabian world and his vast empire, which ran through all Northern Africa until Spain in Europe.

Here there is an important change in the technique. Arabs, not having many fresh plants, started to use clothe fibers and to recycle materials like old carpets, tapestry or damaged cane products. Pulp then obtained produced a finer paper but with a shorter life; also they incorporated starch, which improved its resistance to the stroke of writing. The first workshop installed in Europe was in the Hispanic Arabian city of Cordoba in AD1036.

Perhaps it is a good moment to start explaining what is paper and how does it work. It is a irregular structure formed by entangled fibers in a paste which is hydrated and left decant in a layer relatively homogeneous. The size of the fibers plays a main part to achieve some properties in the paper; long fibers will give it strength and rigidity, but with a rough finish, and short fibers will produce fine paper, formed, flexible, textured and opaque, but not resistant, better for writing. In mixture of both fibers lies the secret to obtain specific results.

With Crusades the manufacturing process arrived to Italy, country where it was incorporated to it a glossy finish with animal grease that gave paper a great surface resistance, which allowed the sharp scribe's pens (made from feather) to write without wrapping it, this made the parchment to disappear very quickly from Europe. The writing technique with feather, dominant in Europe, against the calligraphic brush painted one in the East, determined the final differences between European and Chinese-Japanese paper (2).

With the creation of the printing press on XVth Century, needs of paper grew explosively and clothing resources started to lack, and also hands to do it. In 1798, french Nicholas Louis Robert created the first effective paper machine, which was improved later on 1803 by english brothers Henri and Sealy Fourdrinier. They incorporated on 1840 the crushing of wood to the making process of the pulp. Finally, on 1850, the chemical process to produce pulp was created, which made the production much cheaper. On 1852 Meillier discovered cellulose and Tilghman patented the process to obtain it from wood. Just on 1853, the circle was closed, when paper machines arrived to China and Japan, country that produces the 15% of world's paper needs.

How much knows an origamist about the paper he uses, how it was made, what's the secret that keep it tight and how to select the best for their purposes? And what about the making processes of paper and the ecological problems they mean to nature?

So I decided to do some research.

Maybe a good starting-point should be what paper is not. Word came from latin papirus which signed the plant which were used by the egipcians to make their famous writing rolls .. However, yet the principle is the same, paper we know and use today doesn't have its origins there. Papirus is a plant with long leafs, soft stalk and a triangular wide base and the rolls were made directly from its medulla, a paste which is spread over molds and hydrated with water, pressed and the left dry, to finally be rubbed with ivory or shell to soften its surface. Its origins goes back until 3000 BC and its use s to Greece and the entire Rome Empire until the Vth century. After that, writing was done over parchments, made from fine layers of cow, sheep or ram leather(1).

The true origin for paper lies on China. Around AD 105, emperor Ho Ti ordered his eunuchs chief Tsai Lun the study of new materials for writing, since the wood tablets and silk patches were unpractical for the growing usage of writing. His work concluded with the making of a vegetable pulp made with fibers from bamboo cane, mulberry and other plants, along with the development of a procedure for the making of the paper, which was kept absolutely secret for more than 500 years.

Only after AD 500 the technique of paper making passed to Korea and in AD610, priest Ramjing traveled to Japan for bringing assessment in the production of paper; both countries will upgrade it according to their own resources and technology (in AD700 rice flour was added to the pulp). In 750 it passed to Central Asia, Tibet and India, to finally reach the Arabian world and his vast empire, which ran through all Northern Africa until Spain in Europe.

Here there is an important change in the technique. Arabs, not having many fresh plants, started to use clothe fibers and to recycle materials like old carpets, tapestry or damaged cane products. Pulp then obtained produced a finer paper but with a shorter life; also they incorporated starch, which improved its resistance to the stroke of writing. The first workshop installed in Europe was in the Hispanic Arabian city of Cordoba in AD1036.

Perhaps it is a good moment to start explaining what is paper and how does it work. It is a irregular structure formed by entangled fibers in a paste which is hydrated and left decant in a layer relatively homogeneous. The size of the fibers plays a main part to achieve some properties in the paper; long fibers will give it strength and rigidity, but with a rough finish, and short fibers will produce fine paper, formed, flexible, textured and opaque, but not resistant, better for writing. In mixture of both fibers lies the secret to obtain specific results.

With Crusades the manufacturing process arrived to Italy, country where it was incorporated to it a glossy finish with animal grease that gave paper a great surface resistance, which allowed the sharp scribe's pens (made from feather) to write without wrapping it, this made the parchment to disappear very quickly from Europe. The writing technique with feather, dominant in Europe, against the calligraphic brush painted one in the East, determined the final differences between European and Chinese-Japanese paper (2).

With the creation of the printing press on XVth Century, needs of paper grew explosively and clothing resources started to lack, and also hands to do it. In 1798, french Nicholas Louis Robert created the first effective paper machine, which was improved later on 1803 by english brothers Henri and Sealy Fourdrinier. They incorporated on 1840 the crushing of wood to the making process of the pulp. Finally, on 1850, the chemical process to produce pulp was created, which made the production much cheaper. On 1852 Meillier discovered cellulose and Tilghman patented the process to obtain it from wood. Just on 1853, the circle was closed, when paper machines arrived to China and Japan, country that produces the 15% of world's paper needs.

Bibliography (in Spanish):

(1) http://www.papelnet.cl/papel/papel.htm

(2)http://www.papelerapalermo.com/oficios/art-sobre-como-llego-el-papel.asp